What is oven spring in sourdough?** Oven spring is the rapid rise your bread gets in the first 10 to 20 minutes of baking. It’s when your flatish dough ball puffs up like magic in the hot oven. It happens because trapped gases inside the dough expand quickly in the heat. A good oven spring means a light, airy loaf with a nice open crumb inside. It is one of the most exciting parts of baking sourdough!

Image Source: www.pantrymama.com

Grasping What Oven Spring Is

Picture your sourdough dough before it goes into the oven. It might look a bit flat or just softly rounded. Now, picture it a short time later, tall and proud. That big change is oven spring.

Why does this happen? Your dough holds tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide gas. This gas is made by the yeast in your starter during fermentation. When the dough hits the hot oven, the gas inside those bubbles gets bigger fast. Also, any water in the dough turns into steam, which also expands.

For your dough to trap all that expanding gas and steam, it needs a strong structure. This structure is built by something called gluten. Think of gluten like a stretchy net. If the net is strong and elastic, it can hold the puffing bubbles. If the net is weak, the bubbles escape, and you get less rise.

So, great oven spring comes from two main things:

* Lots of gas made during fermentation.

* A strong, stretchy gluten network to hold the gas.

Getting amazing oven spring isn’t just luck. It’s about doing each step of the sourdough process well. Let’s look at the key things that make it happen.

Step One: A Lively Active Starter

Everything starts with your starter. Your sourdough starter is a mix of flour and water that has friendly wild yeast and good bacteria living in it. These tiny helpers eat the flour and make gas and acids.

A strong, active starter is super important. It needs to be full of energy to create lots of gas during fermentation. If your starter is weak, it won’t make enough gas. This means less puff later on, no matter what else you do.

How do you know if your starter is active?

* It should double or even triple in size after you feed it.

* It should be full of bubbles, both big and small.

* It should smell pleasantly tangy, not like nail polish remover.

* It should pass the float test.

Checking Your Starter’s Strength

The float test is simple. Take a tiny bit of your starter when it’s at its peak (bubbly and active, often a few hours after feeding). Gently drop it into a glass of water. If it floats, it’s ready to bake with! If it sinks, it might need another feeding or two to become strong enough.

Make sure you use your starter when it’s at its peak activity for your dough. This is usually when it has peaked in size and is just starting to fall a little. Using it too early or too late can mean less gas production.

Step Two: Building Strength with Gluten Development

Gluten is the protein network in your dough that gives it structure and elasticity. It’s what allows the dough to stretch and hold the gas bubbles. Without enough gluten development, your dough will be flat and heavy, like a pancake, not airy like good sourdough.

Gluten forms when two proteins in flour (glutenin and gliadin) mix with water and are worked. Kneading or folding the dough helps these proteins link up and form that stretchy network.

With sourdough, we often use a gentler method than hard kneading. This method uses time and simple movements called stretch and folds.

Performing Stretch and Folds

Stretch and folds are easy. After you mix your dough ingredients (flour, water, salt, and starter), you let it rest for a bit. Then, you wet your hand slightly. Grab one side of the dough, stretch it up gently, and fold it over the center. Turn the bowl a quarter turn and repeat with the next side. Do this four times total to complete one set.

You usually do several sets of stretch and folds during the first part of the fermentation period (bulk fermentation). The number of sets depends on the dough’s hydration (how much water is in it) and the type of flour. Higher hydration doughs or doughs with weaker flour might need more sets.

Why stretch and folds help gluten:

* They line up the gluten strands, making the network stronger.

* They trap air, which feeds the yeast.

* They make the dough smooth and elastic.

You’ll feel the dough change as you do the stretch and folds. At first, it might be shaggy and break easily. After a few sets, it will become smooth, stretchy, and resist tearing. This tells you the gluten is building strength. This strong gluten structure is vital for trapping the gas needed for oven spring.

Step Three: The Importance of Sourdough Fermentation

Sourdough fermentation is the magical time when your starter’s yeast and bacteria work on the dough. This is where flavor develops, and gas is created. It has two main parts: bulk fermentation and cold proofing.

Mastering Bulk Fermentation

Bulk fermentation is the first long rise of the dough after mixing and stretch and folds. It happens at room temperature. This is where the dough gains volume, develops flavor, and builds more strength.

This stage is critical for oven spring. The yeast are busy making gas, and the gluten network is relaxing and becoming more extensible (stretchy).

Knowing when bulk fermentation is done is tricky but key. If you stop too early, your dough won’t have enough gas or strength. If you go too long, the gluten can start to break down, and the dough will lose structure.

Signs bulk fermentation is done:

* The dough has increased in size (usually 30-50% increase, depending on temperature and recipe).

* It looks bubbly on the surface and feels airy.

* It passes the “jiggle” test: when you gently shake the bowl, the dough jiggles like jelly.

* It passes the “poke” test: when you gently poke the dough with a wet finger, the indentation slowly springs back about halfway.

Temperature greatly affects how fast bulk fermentation happens. A warmer room means faster fermentation. A cooler room means slower. Many recipes give a time, but it’s better to watch the dough itself. It’s often said to ferment until the dough “feels alive.”

Getting this stage right is vital. Too little fermentation means not enough gas. Too much means a weak structure that can’t hold the gas. Both lead to less oven spring.

The Power of Cold Proofing

After bulk fermentation and shaping, the dough often goes into the fridge for cold proofing. This slow, cold rest is a game-changer for oven spring and flavor.

Why cold proofing helps oven spring:

* Slows Fermentation: The cold slows down the yeast’s gas production. This prevents the dough from over-proofing before baking.

* Strengthens Gluten: The cold temperature helps the gluten network become firmer and easier to handle. This makes scoring easier and helps the dough hold its shape in the oven.

* Develops Flavor: The slow fermentation process in the cold develops more complex, sour flavors.

Dough often proofs in the fridge for anywhere from 8 to 48 hours, or even longer. The longer cold rest builds more structure and resilience. When you take the cold dough out of the fridge and put it straight into a hot oven, the sudden temperature change causes a huge burst of gas expansion, contributing significantly to oven spring. Warm dough might already have lost some of its gas or be too relaxed to spring as much.

Step Four: Careful Sourdough Shaping

Shaping your dough before proofing is more than just making it look nice. It’s about creating tension on the outside of the dough. This surface tension is like a skin that holds the dough’s shape during proofing and baking.

A well-shaped loaf has a tight outer layer and an even structure inside. This tension helps push the dough upwards during oven spring instead of letting it spread outwards.

Shaping Techniques

There are many ways to shape sourdough, like making a round loaf (boule) or an oval one (batard). The key is to use gentle but firm movements to stretch the outer surface while tucking the rest of the dough underneath.

Tips for good shaping:

* Work on a clean, lightly floured surface.

* Be quick but careful. Don’t degassing the dough too much.

* Use your hands or a bench scraper to create tension by pulling the dough towards you or pushing it away.

* Aim for a smooth, tight outer skin.

* Once shaped, the dough should feel taut and hold its shape well.

Shaping also helps redistribute the gas bubbles evenly throughout the dough. A well-shaped dough is ready to hold all the gas that will expand in the oven.

Step Five: Strategic Sourdough Scoring

Scoring is cutting the surface of the dough just before baking. It’s usually done with a sharp blade called a lame (pronounced “lahm”). Scoring is crucial for controlling oven spring.

Think of scoring as making planned weak spots in the dough’s surface. Without scoring, the crust would harden quickly in the oven, and the expanding gases would burst through wherever they find the least resistance, often in messy, uncontrolled ways.

Scoring directs the expansion. It allows the dough to open up along the cuts. This helps the dough rise taller and creates those beautiful “ears” or flaps on the crust.

Scoring for Maximum Spring

- Use a very sharp blade: A sharp lame glides through the dough without tearing. A dull blade can drag the dough and hurt the structure.

- Make clean cuts: Be decisive and confident with your cuts.

- Angle your cuts: Cutting at an angle (around 30-45 degrees) helps create an “ear.” This is because the dough peels back along the angled cut as it rises.

- Depth matters: Cuts that are too shallow won’t allow enough expansion. Cuts that are too deep might make the loaf spread too much. A depth of about 1/2 inch to 3/4 inch is often good.

- Score cold dough: Dough straight from the fridge is firm and easier to score cleanly.

The pattern you score doesn’t just look nice; it affects how the loaf opens. Simple scores, like a single long slash or a cross, often give the most directed spring. More complex patterns can sometimes restrict spring slightly if they cut through too much surface tension.

Step Six: Creating the Right Baking Environment: Steam Baking Sourdough

Steam is a secret weapon for amazing oven spring. When your dough first hits the hot oven, the outside crust starts to form immediately. If the crust hardens too fast, it becomes rigid and prevents the dough from expanding fully.

Steam keeps the surface of the dough moist and flexible for the first part of the bake. This lets the dough expand freely during the oven spring phase. Once the dough has reached its maximum height, the steam evaporates, and the crust begins to set and brown.

How to Create Steam in Your Oven

There are several ways to add steam for steam baking sourdough at home:

- Dutch Oven: This is the most common and easiest way. The lid traps the moisture released by the dough itself, creating a steamy micro-environment around the loaf.

- Steam Pan: Place a tray filled with water or ice cubes on a rack below your baking stone or steel. The heat creates steam.

- Spraying Water: Some bakers spray water on the oven walls just before closing the door. Be careful not to spray the oven light or glass.

- Hot Rocks/Chains: Pouring water onto preheated rocks or metal chains in a tray creates a lot of steam quickly.

Using a Dutch oven or steam pan usually provides more consistent and longer-lasting steam than just spraying. For great oven spring, steam is non-negotiable.

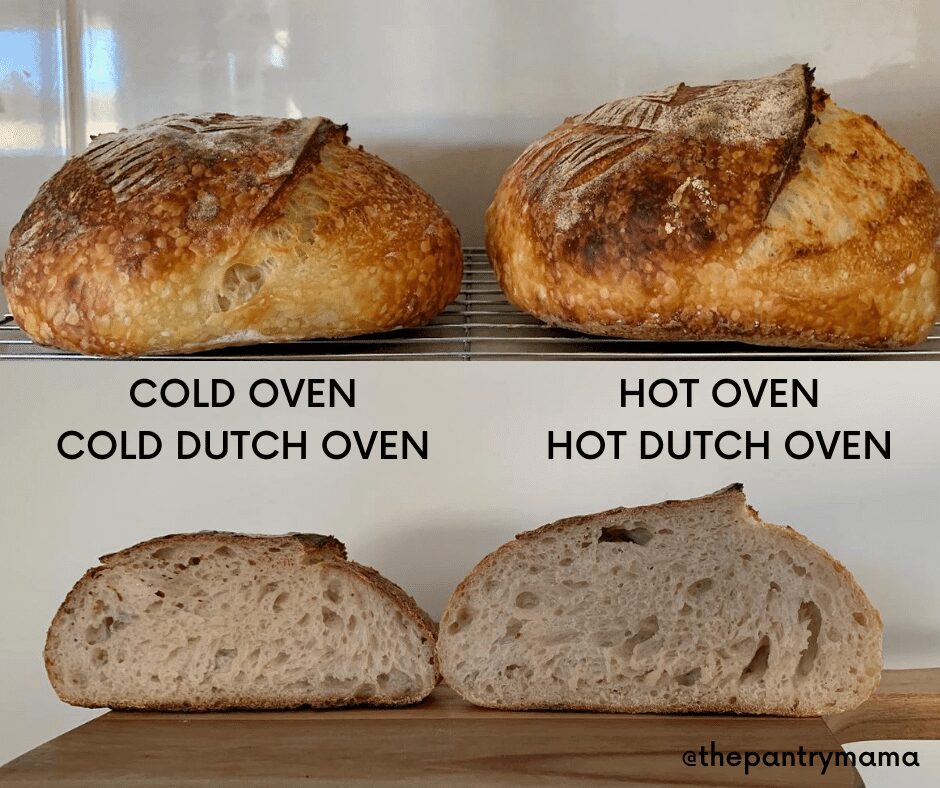

Step Seven: The Magic of Dutch Oven Baking

Using a Dutch oven is arguably the simplest and most effective way to bake sourdough at home, especially for maximizing oven spring.

A Dutch oven is a heavy pot with a tight-fitting lid. You preheat it in the oven at a high temperature. When you put your shaped dough inside and cover it, the lid traps all the moisture coming out of the dough as it heats up.

This creates a perfect steamy environment right around your loaf for the crucial first 15-20 minutes of baking. This is exactly the steam baking sourdough needed for the crust to stay soft and let the dough spring up fully.

After the initial spring, you remove the lid. This allows the moisture to escape, the crust to dry out, and the loaf to brown nicely.

Steps for Dutch Oven Baking

- Place your Dutch oven (with the lid on) in your oven.

- Preheat your oven and the Dutch oven to a high temperature (often 450-500°F / 230-260°C). Let it preheat for at least 30-60 minutes to ensure the pot is screaming hot.

- Carefully take the hot Dutch oven out of the oven (use thick oven mitts!).

- Remove the lid.

- Gently place your shaped and scored dough into the hot Dutch oven. You can use parchment paper to help lower it in easily.

- Put the lid back on tightly.

- Place the Dutch oven back in the oven.

- Bake with the lid on for the first part (e.g., 15-20 minutes) to trap steam and encourage oven spring.

- Remove the lid.

- Continue baking uncovered for the rest of the time (e.g., 20-30 minutes) until the crust is deeply golden brown and the internal temperature is around 200-210°F (93-99°C).

Using a Dutch oven simplifies the steam aspect and provides intense heat from all sides, which is excellent for spring and crust development. If you don’t have a Dutch oven, you can still get good results using a baking stone or steel with a steam pan, but it requires more effort to create enough steam.

Summarizing the Path to Peak Spring

Achieving impressive oven spring comes down to a chain of events, each link needing to be strong.

- Active Starter: Provides the gas.

- Gluten Development (with Stretch and Folds): Builds the structure to hold the gas.

- Sourdough Fermentation (Bulk Fermentation): Creates enough gas and matures the dough; getting the timing right is key.

- Cold Proofing: Strengthens the dough structure and primes it for rapid expansion in the heat.

- Sourdough Shaping: Creates surface tension to direct the rise upwards.

- Sourdough Scoring: Provides controlled escape routes for gas, guiding the expansion.

- Steam Baking Sourdough (often in a Dutch Oven): Keeps the crust soft so the dough can expand fully before setting.

If any of these steps are weak, your oven spring will suffer. For example, even with perfect shaping and scoring, a weak starter or under-fermented dough won’t have enough power to rise. Or, great fermentation and a strong starter won’t matter if your shaping is poor or you don’t have steam in the oven.

Troubleshooting Common Oven Spring Issues

Sometimes, even if you try hard, your loaf doesn’t spring much. Here are some common reasons why and how to fix them:

| Issue | Possible Cause | How to Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Little to no oven spring | Weak active starter | Feed your starter more often until it consistently doubles/triples. |

| Little to no oven spring | Insufficient bulk fermentation | Let the dough ferment longer; watch the dough (poke test, jiggle) not just the clock. |

| Little to no oven spring | Over-proofed dough (bulk or cold proofing) | Reduce fermentation time or temperature; shape sooner. |

| Loaf spreads outwards, not upwards | Weak gluten development | Do more stretch and folds; consider using a bread flour with higher protein. |

| Loaf spreads outwards, not upwards | Poor sourdough shaping | Practice shaping techniques to create more surface tension. |

| Loaf spreads outwards, not upwards | Insufficient cold proofing (too short or warm) | Ensure the dough is truly cold (fridge temp below 40°F/4°C) and proofs for enough hours. |

| Crust hardens fast, restricts spring | Not enough steam during baking (or no Dutch oven) | Use a Dutch oven correctly or ensure your steam method (pan, rocks) works well for the first 15-20 min. |

| Scored cuts don’t open well | Dough not cold enough; dull scoring blade | Score dough straight from the cold fridge; use a new, sharp lame. |

| Crumb is dense, not airy | Combination of weak starter and/or under-fermentation/proofing | Focus on getting the starter very active and correctly timing bulk fermentation. |

Getting great oven spring is a journey. Each bake teaches you something. Pay attention to your dough at each stage. How does it feel? How does it look? These observations are your best guides.

Frequently Asked Questions

How important is temperature for sourdough fermentation?

Temperature is very important! Warmer temperatures speed up yeast activity and fermentation. Cooler temperatures slow them down. You need to adjust your bulk fermentation time based on the temperature of your kitchen. Cold proofing in the fridge uses low temperature to slow fermentation way down.

Can I get good oven spring without stretch and folds?

Stretch and folds are a very effective way to develop gluten in sourdough. While some methods use only time (no-knead), stretch and folds actively build the strong network needed to trap gas for good oven spring, especially with wetter doughs. They are highly recommended for improving spring.

Does the type of flour affect oven spring?

Yes, absolutely. Flours with higher protein content (like bread flour) develop stronger gluten networks than lower protein flours (like all-purpose or pastry flour). Stronger gluten means better ability to hold gas and thus better potential for oven spring. Whole wheat flours have bran particles that can cut the gluten strands, sometimes reducing spring unless handled carefully or mixed with white flour.

Is a Dutch oven necessary for good oven spring?

While a Dutch oven makes it much easier to get excellent oven spring by creating the perfect steamy environment, it’s not strictly necessary. You can use other methods for steam baking sourdough, like a baking stone/steel with a dedicated steam pan, but they can be less effective or require more effort to maintain high humidity around the loaf. A Dutch oven is the simplest path to consistent results.

My dough spreads flat after shaping. What’s wrong?

This often points to either weak gluten development (not enough stretch and folds or wrong flour) or over-proofing during bulk fermentation. If the dough has fermented too long, the structure can break down, making it unable to hold tension during shaping. Ensure your bulk fermentation isn’t going too long and that you are building good strength with stretch and folds.

How does hydration affect oven spring?

Higher hydration doughs (more water) can potentially achieve a more open crumb structure and good spring because there’s more water to turn into steam. However, they are also harder to handle and require very strong gluten development and careful shaping to prevent them from spreading outwards instead of upwards. Lower hydration doughs are easier to handle and shape, making it simpler to build tension, which also helps spring.

Final Thoughts

Getting that beautiful, sky-high oven spring in your sourdough loaf is incredibly satisfying. It’s a sign of a healthy starter, well-developed dough, and careful handling through each step. Focus on making sure your starter is active, building strong gluten development with stretch and folds, correctly timing your bulk fermentation, giving it a good cold proofing period, shaping it with tension, scoring it cleanly, and baking it in a steamy environment, ideally using Dutch oven baking.

Each bake is a chance to learn and improve. Pay attention to what works and what doesn’t. Soon, you’ll be consistently pulling loaves from your oven with the impressive oven spring you’ve been dreaming of! Happy baking!